The referendum held on September 25 in Iraqi Kurdistan triggered a political movement in the entire Middle East, whose outcome is difficult to forecast at this time.

The referendum held on September 25 in Iraqi Kurdistan triggered a political movement in the entire Middle East, whose outcome is difficult to forecast at this time.

It is ironic that in another part of the world, namely Europe, a simultaneous struggle for independence began. Indeed, Catalonia held a referendum on October 1 to leave Spain, when centuries-old frustration came to a head. With almost the same size of the population as Iraqi Kurdistan, 7 to 8 million, Catalonia was brought under Spanish rule in the 15th century, during the reign of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile. The Catalans suffered most under the fascist rule of General Francisco Franco (1938-1975), who went so far as to ban the language, much like the fate of Kurds under Turkish and Iraqi rule, thus threatening to destroy their identity. Catalonia’s referendum sent tremors throughout Europe, especially in Scotland and Belgium, where irredentism is ripe to explode any time.

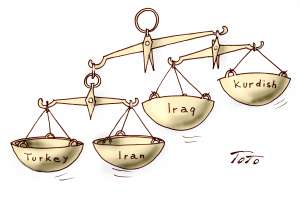

The only difference between Catalonia and Iraqi Kurdistan is that the former faces one opposing force, Spain, while the latter by at least four, and major powers still waiting in the wings: Turkey, Iraq and Iran have all been mobilized to stifle Kurdistan’s aspirations for independence. Syria is too fragmented and weak to join the fray but, in principle, shares the same policy as its neighbors regarding Kurdistan.

Kurdistan’s referendum marks the demise of the Sykes-Picot Treaty of 1916 and opens a Pandora’s box in reviving the Treaty of Sevres of 1920, in which Armenia holds a share, too.

The Kurds in Iraq took a few very strategic measures to consolidate their internal base on the domestic front and to occupy the oil-rich region of Kirkuk after helping Iraq to defeat ISIS forces occupying that city.

Iraqi Kurdistan is ruled by two families, Talabanis and Barzanis, who to this day, maintain their separate militias which have been at odds most of the time. Those forces, called Pesh Mergas, concluded an understanding on the domestic front and helped the US forces in clearing ISIS from the Iraqi territory. A total of 5.2 million (or 72 percent) of voters participated in the referendum, with 93 percent casting a “yes” vote. The conclusion of the referendum vote does not automatically mean independence. It only gives a mandate to begin negotiations with the national government in Baghdad, whose prime minister, Haidar Al-Abadi, is in no mood to negotiate. He is asking the results of the vote to be annulled before sitting at the negotiation table.

Turkey adamantly opposes independence for Kurdistan for obvious reasons. Thus far, Ankara has been dealing with Iraqi Kurdistan’s regional government, ignoring Baghdad’s warnings. Kurdistan’s oil was flowing to Turkey, generating 80 percent of the regional government’s budget. While Mr. Abadi is seeking control of Irbil and Suleymanya airports, Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is threatening that the “spigots of the pipelines are in our hands.”

Iran, Turkey’s archrival in the region, has joined the latter in war games on the Kurdistan borders. Thus, all regional countries are concerned that Kurdistan’s independence will inexorably fan the aspirations of Kurds in their respective countries to fight for independence. The Kurds are estimated to be 30 to 40 million strong, living in Iraq, Syria, Iran and Turkey. The latter has been cracking down on Kurds for the past three decades.

There is general consensus among political observers that war against Kurdistan is not imminent, mainly for the fact that major powers have already made huge investments in Kurdistan. But Turkey may instigate the local Turkmen who have always seemed to act as the fifth columnists to stir some trouble in Kurdistan. Also, Mr. Abadi’s weak government may attempt to retake Kirkuk from Kurdish control.

Former French Foreign Minister Bernard Couchner has stated that Kurdistan’s independence may bring stability to the region. However, Kurdistan’s neighbors do not seem to share that view as they intensify their war of words.

In anticipation of Kurdistan’s forthcoming independence, several major powers have ventured to make huge investments. Thus, Kurdistan’s regional government has signed deals with Exxon Mobil (US), Total (France), Taqa (United Arab Emirates) and Gazprom (Russia). It would be foolhardy for any party to mess with these interests by engaging in military action.

It was the psychological moment for Masoud Barzani to hold the Kurdish referendum, as the central government in Iraq is still fighting to recover the last remaining pieces of territory from ISIS and can ill afford to challenge battle-hardened Pesh Merga fighters on the battlefield.

While keeping the PKK Chief Abdullah Oçalan in jail, Turkey had granted the status of Kurdish leadership to Masoud Barzani, who now in disappointment states that he had pinned hopes on Turkey which at this time has made a 180-degree turn regarding its Kurdish policy by opposing the referendum. Iraqi Kurds had paid a heavy price to be in good graces of Ankara, by fighting their brethren in the ranks of PKK.

While regional forces have met the referendum with hostility, the major powers have demonstrated a benign tolerance. The US has sided with Turkey and Bagdad, deploring the referendum, but in the meantime vowing to continue supporting the region militarily. Moscow also has expressed “concern” over the referendum, but beyond that it has kept a meaningful silence. The most assertive support came from Israel, for obvious reasons. For a long time, Israel was isolated. Although it has established diplomatic relations with Egypt and Jordan, that was not considered a breakthrough. Now, Israel has set up shop in Kurdistan and has been supplying arms and supporting the region militarily, because for the first time, it is extending its power all the way to the gates of Iran, a major Shiite power antagonistic to the Jewish state. Israeli analyst Avigdor Eskin has outlined his country’s strategic interests in Kurdistan, in an interview with Armenian TV I. In that interview, he confessed that Israel has been supporting the Kurds and supplying them with arms since the 1960s, which means that Kurdish rebellions against Saddam Hussein might have been instigated by Israel. Mr. Eskin also gave high marks to Armenia’s cautious policy in this matter.

Sooner or later, the US will line up with Israel, because in the Middle East, Israel’s position is the one the US follows. Washington has not demonstrated an independent policy there for a long time.

Mr. Erdogan, by straining relations with the West, all but forced Europe and especially the US to depend on the Kurds. That is why Mr. Erdogan has been desperately embracing Vladimir Putin, who is on a state visit in Ankara these days.

In the turmoil of the Middle East, the Kurds have been successful in maintaining stability in Iraqi Kurdistan and the Rajova regiona, in Syria, right on the Turkish border. This has meant two things: that the Kurds can rule themselves and that they can be reliable partners for the West.

Taking advantage of the stability in Kurdistan, Iraqi Armenians have gravitated to that region, where even they have representation in the parliament and have fighters embedded with the Kurdish Pesh Merga.

Armenia has adopted a nuanced approach to the entire issue. It maintains friendly relations with Baghdad, but it has also an agreement with Kurdistan to establish diplomatic relations by opening a consulate in Erbil. In deference to Tehran, which opposes the referendum, Armenia’s foreign minister, Edward Nalbandian, has come up with a prudent announcement, stating “ We do hope that Iraqi government and regional authorities in Kurdistan do not spare energies to avoid conflicts.”

The situation in Artsakh is totally different. The government in Stepanakert has congratulated the country for the outcome of the referendum and expressed full support for Kurdish independence. Kurdistan’s independence reinforces the principle of self-determination for ethnic minorities, pundits’ cautions aside that each case is different. The principle of self-determination is based on the same tenet in international law. Only political factors surrounding the issues determine the outcome in each case.

An extensive BBC article titled “We don’t need to go from Kurdistan to Catalonia,” referred to the Artsakh case, suggesting “regardless of international recognition, self-proclaimed governments can exist.”

Kurdistan’s independence will change realignments in the Middle East, moving closer Sunni Turkey to Shiite Iran and Baghdad. Israel will further expand its dominance in the region with tacit acquiescence of Sunni kingdoms on the Arabian Peninsula.

Kurdistan’s referendum has triggered an entire new political game in eh Middle East.

When the dust settles, a new nation will be drawn on the map. Edmond Y. Azadian