Common folks in Egypt have a very keen sense of humor. They can create anecdotes to render the most complex political issues into simple humorous stories. One such anecdote is about President Anwar Sadat, who succeeded President Gamal Abdel Nasser. According to the anecdote, Sadat inherited Nassar’s chauffeur, who is supposed to drive him from his residence to the presidential palace. On the first day, the driver stops at a crossroads and asks the new president which way to take. After finding out that his predecessor used to take a left turn, he orders the driver to “signal left and turn right.”

Common folks in Egypt have a very keen sense of humor. They can create anecdotes to render the most complex political issues into simple humorous stories. One such anecdote is about President Anwar Sadat, who succeeded President Gamal Abdel Nasser. According to the anecdote, Sadat inherited Nassar’s chauffeur, who is supposed to drive him from his residence to the presidential palace. On the first day, the driver stops at a crossroads and asks the new president which way to take. After finding out that his predecessor used to take a left turn, he orders the driver to “signal left and turn right.”

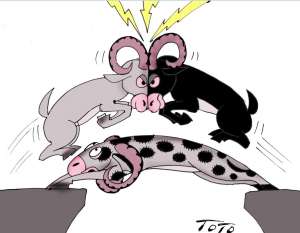

In a way, this situation also characterizes Armenia’s foreign policy. Outwardly, relations seem normal. From the prime minister down to the foreign minister, all exalt Armenian-Russian relations. They reaffirm the importance of the Russian 102nd military base in Armenia and they value Armenia’s participation in the collective security pact led by Russia; yet there is an unease in the air. While on the official level, pronouncements are rare, the news media are awash with criticism and counter criticism, giving the impression that the parties are at each other’s throats.

During the previous administration, media criticism – and caustic ones at that, was permissible. As a journalist, even the current prime minister did not pull his punches. But the Velvet Revolution, which has unified the population and has offered a hope for a better future, has also endowed the new administration with an aura of infallibility. It is within this paradigm that we need to analyze Armenia’s foreign policy.

Now that Armenia has overthrown bloodlessly the corrupt regime, it has all the right to guard its sovereignty jealously. But that sovereignty has its own determinants, one of which is Armenia’s relevance in the balance of power of the region. In Europe, 28 nations have forfeited their sovereignty to a certain measure, for the common good. That’s statecraft which develops with historical experience.

At this time, Armenian-Russian relations seem to be at a critical juncture. The Kremlin has been watching all the movements and actions of the new government in Yerevan, in domestic and foreign policy, and has been reacting nervously.

Robert Kocharyan’s incarceration and his pending trial do not bode well for Moscow, because he has always served as a pillar of Russian influence in Armenia. So far, Moscow has tempered its reaction in Kocharyan’s case, considering it a domestic issue. However, when Yuri Khachaturov’s case arose, official Moscow spoke. The latter was the commander of the Yerevan Garrison during the March 1 events of 2008, when 10 people died and many others were wounded. Kocharyan is accused of “overthrowing the constitution” by ordering the army to move. General Yuri Khachaturov is considered the executor of Kocharyan’s order. Cognizant of the delicate nature of Khachaturov’s case, Armenia’s government dealt rather deftly with it and released him from jail on bond, allowing him to travel to Moscow to continue serving his term as the secretary general of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO).

CSTO is in a way, the counterpart of the NATO military alliance. Jens Steltenberg is NATO’s secretary general. Imagine if the latter’s home country, Norway, recalled him for criminal investigation. The entire structure of NATO would experience a shake-up. In Khachaturov’s case, the Armenian government is pondering whether to recall him, after hardly serving half of his three-year term, and replace him with former defense minister Lieutenant General Vagharshak Harutyunyan.

It was indeed a special consideration for Armenia to have its representative in that very sensitive position. CSTO does not have as solid a structure as NATO, where there is virtually universal commitment to its goals and policies. CSTO has a looser structure: of its six member countries, two (Belarus and Kazakhstan) have closer relations with Azerbaijan than Armenia, while Azerbaijan has turned down the offer to join that military alliance. The secretary general has the command of flow of all information within the alliance and has control of military procurement. Unfortunately, it is not Armenia’s choice to replace Khachaturov. It is believed that Belarus has already lined up its candidate for that position.

For a certain time Kremlin was observing a patient silence, while the Russian media was raging with a scathing campaign against Armenia. Khachaturov’s case was the straw that broke the camel’s back.

The Russian influential publication Kommersant states that Russia is particularly irritated by the accusations laid against Secretary General Yuri Kachaturov, because Moscow believes it was a serious blow to the authority of CSTO.

In the wake of the current row, rumors went around that Russia was halting its deal with Armenia to deliver $100 million worth of military aid. Later on, Armenia’s Defense Minister Davit Tonoyan contacted Russia’s Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin, who assured that the deal was still on.

Sergei Lavrov is Kremlin’s top diplomat, and his words carry weight. He blamed the new government in Armenia, stating that its actions do not correspond to the promises made earlier. He added that “Russia, as an ally to Yerevan, has always been interested in the stability of the Armenian state and Russia is concerned over developments in Armenia.” Lavrov hopes that the matter will be settled “constructively.”

Nikol Pashinyan did not react immediately. But commentators believe that Pashinyan’s call for a general rally on August 17, which coincides with his 100th day in power, was his response, because that day he may come up with some major policy statements. But the Armenian media reacted violently. The newspaper Zhoghovurd wrote: “Lavrov’s statement is a blatant attempt to interfere in the country’s domestic affairs. It was the first ever sign hinting Russia’s disagreement with Armenian politics since the Velvet Revolution.”

Armenia’s news media are abuzz with angry reactions. Commentators have been writing under pen names like Sargis Artsruni and Armen Amatuni, people who may prove to be officials in the government. For example, Sargis Artsruni writes: “Lavrov’s announcement is a hostile act, which is unleashing a war against Nikol Pashinyan’s government, mobilizing the revanche of the counter revolutionary forces in the country.”

Another writer, Aram Amatuni, says “Thus, Nikol Pashinyan’s call for a rally turns out to be response to the announcement of the Russian foreign minister. At that rally, Yerevan will demonstrate the level of its legitimacy, to remind Russia that this time around it has to deal with a different kind of government in Armenia. And as a consequence, it has to forget old methods of dealing with Armenia and has to adopt a new manner of approach.”

If the above statements are considered hysteria in the news media, a consummate diplomat’s position is not any different. “Russia should not have interfered in Armenia’s domestic political affairs to criticize the authorities for the arrest of the Collective Security Treaty Organization’s top official,” Ambassador Arman Navasardyan said, commenting on Foreign Minister Lavrov’s statement. “What matters here are mutual interests. Armenia’s importance for Russia is almost as great as what Russia represents for Armenia. Should Russia lose Armenia, it will also lose the South Caucasus.”

It looks like below the surface of these exchanges, Russia has deeper concerns: Armenia’s rapprochement with Brussels, its participation in NATO military exercises in Georgia, and now the new movement of the US Armenia Caucus, hand-in-hand with advocacy groups, to arrange a Trump-Pashinyan meeting are all signs of Armenia’s political re-alignment.

Armenia deserves to accede to full democracy, eradicating corruption and adopting European standard of governance.

Armenia’s population alone can achieve that goal, without relying on Europe or the West. Adhering to the West has its hazards too. The West is interested in Armenia as much as it can use it as an irritant against Russia. But once Armenia lines up with the West, different circumstances come into play. The West has its own priorities and on that priority list Armenia’s interests will stand below the ones of Turkey as a NATO ally, and Azerbaijan as an energy source. The West did not lift a finger to dislodge Turkey from Northern Cyprus, although Greeks also are partners in NATO. Therefore, Armenia does not stand a better chance than Greece.

Alliance with Russia is not an ideal situation, but there is no ideal situation for a beleaguered country like Armenia.

Pashinyan’s mentor, Levon Ter Petrosyan, once snubbed Moscow at his own peril and we lost two thirds of Karabakh to Azerbaijan.

Armenia’s foreign policy will derive its strength from its rejuvenated domestic policy. And today Armenia is fully geared to achieve that under new rule. Realigning Armenia’s foreign policy should not lead the country to misalignment. Edmond Y. Azadian