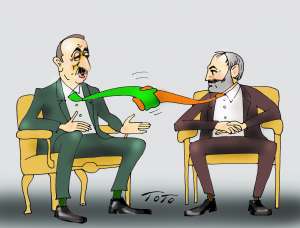

Following their visit to Yerevan and Baku, the co-chairs of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, representing Russia, the US and France, have announced that a summit between Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azeri President Ilham Aliyev is in the offing.

Following their visit to Yerevan and Baku, the co-chairs of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, representing Russia, the US and France, have announced that a summit between Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azeri President Ilham Aliyev is in the offing.

Before that, Armenia and Azerbaijan had been advised to prepare their respective populations for peace, which meant that a compromise had been agreed upon, forcing the parties to accept painful concessions.

As optimism builds in the region through the announcements of major powers, their rosy outlooks are not corroborated by the Baku authorities. Indeed, the spokesperson of the Azerbaijani Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Layla Abdoullayeva, stated that these forthcoming meetings have to secure the liberation of “occupied territories and the return of exiled Azerbaijanis to their homes.”

This type of announcement only dampens hopes for a peaceful settlement.

As if this one-sided declaration was not enough, Ilham Aliyev himself felt the need to make a more incendiary announcement, stating that Azerbaijan today is more powerful politically and militarily and is in a position to settle the conflict in its favor.

In his turn, Pashinyan, during his recent trip to Iran, stated that Armenia is ready to resolve the conflict peacefully, but that in view of Aliyev’s bellicose rhetoric, if Baku resorts to using force, Armenia is ready to respond in kind.

Though the OSCE and other regional powers have been at work to create an atmosphere of peace, the parties of the conflict are very far away from that mood.

Since assuming power, Pashinyan has been trying to revive another agenda, which had been active until President Robert Kocharyan’s term, namely the participation of a Karabakh representative in the negotiations.

Baku is dead-set against that idea. “The format of the Karabakh conflict negotiations are fixed and they cannot be changed,” announced Hikmet Hajiyev, the head of the Presidential Commission on Foreign Affairs, and concluded, “The attempts by the Armenian government to change the format of negotiations lead nowhere other than to a dead end.”

Pashinyan’s logic for inviting the Karabakh representatives to the negotiation table is that he himself cannot represent Karabakh because people in that region have not voted for him, and therefore have not offered their mandate to negotiate on their behalf.

Azerbaijan offers a cynical twist to that logic with a counteroffer. Since Karabakh Armenians have not mandated Pashinyan to represent them at the negotiation table, they can join the expelled Azeris from Karabakh and as citizens of Azerbaijan, they can mandate all the present and former residents of Karabakh. This means that Pashinyan’s strategy will not be able to bring Karabakh representatives to the table. Instead, it will serve as an impediment to the process.

In the background of all this rhetoric, the major powers have also indicated some changes. American analysts believe that Moscow’s policy has shifted towards Baku, while on the other hand, the Carnegie Foundation has revealed in a statement that the US has decided to offer generous assistance to Armenia to consolidate the foundations of democratic rule in that country, to serve as a role model to other authoritarian rulers in the region. If this last comment is true, it means that the US has been using a carrot and stick policy with regards to Armenia. While US National Security Advisor John Bolton had warned Armenia to shut its borders with Iran, this generous offer comes as a surprise because Armenia not only has not shut its border but instead has intensified its ties with that country. Pashinyan’s recent trip to Iran was very prominent both in terms of substance as well as appearance.

As a symbol of Moscow’s sympathy tilt, we may cite the participation of a Russian parliamentary delegation in the commemoration of the “Khojalu genocide” in Baku, which drew a rebuke from Ararat Mirzoyan, the Parliament Speaker, during his official trip to Moscow.

As we can see, the situation is always in flux in the region as alliances and antagonisms shift, driven by changing political outlooks.

Iran has stuck to a policy of strict neutrality between Armenian and Azerbaijan, but this time around, Tehran gave the red-carpet treatment to Armenia’s prime minister. Baku was carefully watching Pashinyan’s every move in Iran and was hoping that the Islamic Republic’s Supreme Spiritual Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, an ethnic Azeri, who offers the final blessing to any deal, would not receive Pashinyan. However, he received the Armenian leader enthusiastically, and supported the intensification of relations with Armenia.

During Pashinyan’s visit to Iran, President Hassan Rouhani offered Armenia to serve as a transit country to take Iranian gas to the north. Such a responsible offer would not have been made before receiving Moscow’s and Tbilisi’s consent.

Within this realm, Iran offered to host a conference with the representatives of Armenia, Georgia and Russia to discuss cooperation among the three for gas and electrical strategies.

Iran is wary of Azerbaijan’s relations with the West and its deals with Israel. And as US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s war rhetoric is getting louder, Tehran is suspicious of the Aliyev clan allowing the use of Azerbaijan as a launching pad for an invasion of Iran.

That fear was expressed in a recent speech by a reticent President Rouhani on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution. Referring to the territorial dismemberment of Iran in history, he alluded that a piece of Iran’s territory had been usurped 191 years ago. The reference was to the Treaty of Turkmanchai, according to whose terms Iran lost the territory comprising the Republic of Azerbaijan. Normally, the claims are in reverse. Baku claims Northern Azerbaijan, which is part of Iran. The reference was very symbolic.

After Iran, Pashinyan headed to Brussels to improve relations with the European Union. Armenia is exercising a multi-vector policy.

At this time, Armenia and Azerbaijan are playing a political game similar to a popularity contest, before they meet face to face.

As we can see, there is a web of interlocking interests and conflicting policies which directly or indirectly impact the negotiations of the Karabakh conflict. It is not yet clear when the Pashinyan-Aliyev summit may take place, but certainly all the above developments will interact to influence the outcome of those negotiations. Edmond Y. Azadian