By Benyamin Poghosyan published in The Armenian Mirror Spectator

On September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan launched a military offensive against the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic with one clear goal – to destroy it. It was a logical continuation of Azerbaijan’s decades-long policy, including the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war and the blockade of the Lachin (Berdzor) corridor imposed in December 2022. After 24 hours of intensive fighting, the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic surrendered. A few days later, the large exodus of the Armenian population started, and by the end of September 2023, less than 100 Armenians were left in Nagorno Karabakh. On September 28, the president of the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic signed a decree to dissolve the Republic by the end of 2023.

The reaction in Armenia to these events was somewhat surprising. The government made it clear that Armenia would not intervene to prevent the destruction of Nagorno Karabakh. Most Armenians went to social media, lamenting the lack of actions by Russia, the EU, and the US. Many were genuinely surprised that for Russia and the collective West, geopolitical or economic interests had more value than the fate of 100,000 Armenians who lived in Nagorno Karabakh for the last several millennia.

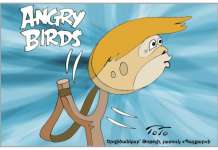

Most Armenians appeared to live in a parallel universe where the world powers were acting based only on values. The second reaction of Armenian society was the quest to find culprits. The list was quite long – starting with Russian President Vladimir Putin and ending with President of the European Council Charles Michel, with Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, and even US President Joe Biden somewhere in the middle. Another trend was to change social media profile photos, putting pictures either taken in Nagorno Karabakh or with cultural and historical monuments of Nagorno Karabakh.

Yes, many Armenians also take part in numerous private initiatives to support the forcibly displaced persons from Nagorno Karabakh, but all know that this will not continue forever. Several months later, many will be overwhelmed by the problems of their daily lives, and few will continue to support Karabakh Armenians, as was the case with the forcibly displaced Armenians from Shushi and Hadrut due to the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war.

What is mainly missing are the debates and discussions on what should be done now, after Azerbaijan finished with Nagorno Karabakh by force. There are two ways forward – the first path is to concentrate on the humanitarian issues of the forcibly displaced persons from Nagorno Karabakh, seeking to accommodate some of them in Armenia and forget about the 32 years of existence of the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic. Part of this strategy is the talk about the “right of return” of Armenians to Nagorno Karabakh and the discussions about to whom Armenia should apply to secure that right – the UN, the EU, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the Council of Europe, the international Court of Justice, the US, or other countries such as France, or, to put this in other words, who should become the “savor of the Armenians” this time.

The problem here is the crystal-clear fact that no Armenian from Nagorno Karabakh can live under Azerbaijani jurisdiction, regardless of any international presence in Karabakh “to secure their rights.” The only way to secure the right of returns of Armenians is to end Azerbaijani control over Nagorno Karabakh, and Armenia can do that only through military means. All other discussions about the international community, international law, and other fascinating terms are simple manipulations for some political gains and political goals, either inside or outside Armenia. Option one is the direct path to very soon transform Nagorno Karabakh into a new “Western Armenia” or “Nakhijevan” with songs, restaurants with Karabakh toponyms in downtown Yerevan, or even some residential areas replicating the names of Karabakh towns or Stepanakert suburbs/neighborhoods.

However, there are other available options. Option two envisages the perception of the fact that the world will pass through a very turbulent one or two decades as a transition is underway from a unipolar system to something different. It is too challenging to assess this new order, but it can be argued that the South Caucasus will be part of this turbulence and transition. Thus, the geopolitics of the South Caucasus will continue to change, including the balance of power and the relations between key players. It fully applies also to the future of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Nagorno Karabakh. However, if Armenia sits and waits, it will probably continue to lose, as it has been losing since 2020.

The first thing which should be done, and it should be done immediately, at least by the end of 2023, is to repeal the decree of the president of the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic on the dissolution of the Republic. Without going into legal battles about the legality of this decree, it is clear that if it is not repealed, it will significantly complicate any actions to reverse the situation beyond 2023. The repeal of the decree will mean that both the president and parliament of the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic will continue to function until spring 2025, as both were elected in the spring of 2020 for five years. They should continue to function in Yerevan, or, if the Armenian government thinks that Azerbaijan will use their functioning as a casus belli to justify its new aggression against Armenia, which Azerbaijan prepares to launch in any case, discussions should be held to find another country which may allow these bodies to function.

Canceling the September 28 decree does not mean Armenia should withdraw from negotiations with Azerbaijan on a peace treaty. An Armenia – Azerbaijan peace treaty, including the recognition by Armenia of the territorial integrity of Azerbaijan within Soviet Azerbaijan borders (86,600 square km.), has nothing to do with the existence of the self-declared Nagorno Karabakh Republic. The Republic should continue to function, and Armenians should be ready to restore it if the necessary conditions emerge amidst the global and regional turmoil. No one can guarantee that these conditions will emerge, but no one can argue that they will not. What should be done is to be ready to use them if they appear, and the first step in that direction is the cancellation of the September 28 decree.