By Benyamin Poghosyan published in The Armenian Mirror of Spectator

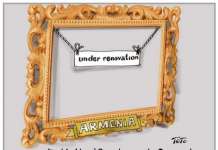

Since the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war, diversification has probably been the most-used term in discussions about the future of Armenian foreign policy. It should be noted that Armenia has sought to pursue a diversified foreign policy since the early years of independence. In parallel with establishing a strategic alliance with Russia, Armenia has launched a pragmatic partnership with the EU and NATO.

Armenia signed its first IPAP (Individual Partnership Action Plan) with NATO in 2005. NATO was actively involved in the defense reforms in Armenia accelerated after 2008, including defense education and strategic defense review.

Armenia joined the EU Eastern partnership initiative in 2009. It failed to conclude the Association Agreement with Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. Instead, it signed the Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement in 2017, now serving as the solid base for Armenia–EU relations.

However, the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war, Azerbaijan’s incursions into Armenia in 2021 and September 2022, and the Russia – Ukraine war made more diversification a necessity. Being bogged down in Ukraine, Russia could not fully implement all its security obligations towards Armenia. At the same time, the growing role of Azerbaijan and Turkey for Russia impacted overall Russian policy in the South Caucasus.

Azerbaijan exploited this situation quite successfully. It imposed a blockade on Nagorno Karabakh in December 2022. It launched a military offensive in September 2023, forcing the dissolution of the self-proclaimed Nagorno Karabakh Republic and the displacement of the entire Armenian population of the region. However, Azerbaijan’s appetite is only growing, and now the targets of Azerbaijan are so-called enclaves and the establishment of routes that will connect Azerbaijan with Nakhijevan and Turkey via Armenia.

Yes, after establishing a checkpoint in the Lachin corridor in April 2023, Azerbaijan dropped demands for an exterritorial corridor via the Syunik province of Armenia. However, Baku still demands special guarantees for the safety of Azerbaijanis who will pass through Armenia. “Special guarantees” is quite a vague term and may be exploited by Azerbaijan in various ways.

As the threat of new military incursions by Azerbaijan remains high, and Russia continues to be distracted by Ukraine while simultaneously seeking to improve its relations both with Azerbaijan and Turkey, Armenia should take robust steps to diversify its foreign and defense policy, seeking to find new sources for arms supplies and political deterrence against Azerbaijan. The steps taken by Armenia in the last year, including the arms supplies deals signed with India, efforts to increase the EU presence in Armenia, and the start of the discussions about potential arms supplies from France, are steps in the right direction.

However, a clear line exists between further diversification of Armenian foreign and defense policy and pursuing an anti-Russian policy, which will bring Armenia into the Russia – West or “democracy vs authoritarianism” war. As Armenia faces significant threats from Azerbaijan and Turkey, including the potential of small or large-scale military invasions, making Armenia another anti-Russian and pro-Western hotspot in the post-Soviet space will significantly increase the security risks for Armenia.

Russia will do everything to prevent domination over Armenia by the West, and the Kremlin has a wide range of options to pressure Armenia. It may use multiple economic leverages, starting from the price of Russian gas and ending with creating obstacles for Armenian businesses to reach Russia, which is the destination of up to 40 percent of overall exports of Armenia. What is more dangerous, Azerbaijan may use these anti-Russian sentiments of Armenia in its negotiations with Russia, portraying Armenia as a “hostile spot for Russia,” which wants to bring the US and EU further into the close vicinity of Russia’s southern borders.

Iran also may not be happy with the potential geopolitical shift of Armenia. Since the end of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Iran has been signaling that it opposes any geopolitical changes in the region. Many in Armenia interpret this only as Iran’s objections to the Azerbaijani attack and occupation of Southern Armenia, but Iran messages also its objections to the U-turn in Armenia’s foreign policy from Russia to the West.

Iran and Russia support establishing a regional format (3+3, or 3+2) for the South Caucasus, circulating the idea that regional problems first of should be solved by regional powers. Azerbaijan and Turkey pushed the idea immediately after the end of the 2020 Nagorno Karabakh war, and Turkey came up with a similar idea after the 2008 Russia – Georgia war. A real or perceived U-turn of Armenia towards the West, while portraying itself as a new launchpad for the West in the South Caucasus, may present Armenia in a negative light for Russia, Iran, and Turkey.

While hoping to increase its influence in the South Caucasus by decreasing Russia’s presence, Ankara does not want to see the West more in the region. Azerbaijan may skillfully use this situation in its bargaining with Russia, Iran, and Turkey, portraying Armenia as the main spoiler in the South Caucasus, which opposes the regional formats and seeks to bring the West deeper into the region. It may create a situation where Russia and Iran will not be against seeing additional harm imposed on Armenia, while Azerbaijan and Turkey will only be happy to do that.

Meanwhile, it should be noted that anti-Russian policy is not a mandatory or necessary condition for the further diversification of Armenian foreign policy. It is challenging to assume that India demands Armenia to become vocally anti-Russian to sell Indian weapons, France requires public steps against Russia for arms supply, or the EU wants anti-Russian statements to provide additional financial support to Armenia or discuss the potential expansion of its monitoring mission.

As the post-Cold War order is waning, and the new order has not emerged yet, the world has entered a period of interregnum. The next decade or even decades will be full of turbulences, conflicts, and the establishment of ad-hoc alliances. In the current situation, Armenia should be cautious not to jump into the middle of the Russia–US war, portraying itself as another fighter against authoritarianism or for democracy. In other words, Armenia should not seek to become a new Georgia in the South Caucasus, repeating Tbilisi’s path of 2004-2012. It will be wiser to look into the example of Georgia in 2022-2023. Georgia has an Association Agreement, Free Trade Area, and visa-free regime with the EU, a strategic partnership with the US based on the charter signed in 2009, a free trade agreement and newly established strategic partnership with China, and growing economic cooperation with Russia.