By Garik Poghosyan published in The Armenian Mirror-Spectator

The dissolution of NKR was a major psychological blow to the Armenian people. The decree spelled the end of Armenian hopes pinned on a Russian peace-keeping force on the ground was a guarantor of the continuation of an Armenian Artsakh (the Armenian name for Nagorno-Karabakh). Around a century ago, Diana Apcar, the honorary consul of the first Republic of Armenia to Japan, nicknamed “the stateless diplomat,” wrote a book, Armenia Betrayed in 1910 published by Yokohama: The Japan Gazette Press. The book described the Armenian massacres in Cilicia in 1909 and the helplessness of the civilian population vis-à-vis the great political game.

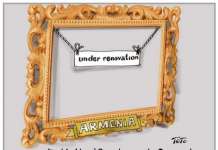

After more than a hundred years, the concept of betrayal seems to be haunting the nation both from within and externally. Much of what domestic political forces and factions have had to quarrel over since the end of the 2020 war in Artsakh has been about betrayal: who betrayed whom, how, when and why. Apparently, what Armenian politics is in dire need of are statesmen who can own up to their wrongdoings. The occasional admission of past mistakes on the part of the opposition seems to be procedural and merely spoken. Consequently, the absence of powerful and united opposition plays into the hands of the current government, which avoids any meaningful discussion of its dramatic trajectory despite the widespread public perception of having political prisoners, mounting foreign debt, a rising crime rate and rampant apathy.

In these circumstances, the fate of the people of the former de facto state of Nagorno-Karabakh is becoming increasingly vague. This article suggests that if the de facto state of Nagorno-Karabakh existed before (the infamous tripartite November 9, 2020 agreement between Armenia, Russia and Azerbaijan that ended the 44-day war, ceded much of what remained under Armenian control to Azerbaijan, trusted the fate of Karabakh Armenians to the Russians and laid the groundwork for the eventual catastrophic exodus of the Armenians), then the recognition of the former NKR is still possible in a reverse order of state-building.

The formula is simple: if de facto states exist on the ground-physically and functionally but lack recognition, then a former de facto state can continue its legal existence through recognition and then claim ownership of the land that was occupied by a colonizing power, in this case, post-Soviet Azerbaijan nostalgic for Stalin’s territorial policies. Thus, the swap we suggest looks into the possibility of recognizing NKR first and then negotiating the territorial reemergence of the former de facto state. In other words, “first de facto, then de jure” is over and “first de jure, then de facto” begins its existence.

An international failure to uphold the rights of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh would mean a carte-blanche for more bloodletting and encroachment on fundamental human rights across the region, something that has the potential of destabilizing the European Union’s eastern and south-eastern frontier in no uncertain terms. The status-quo is ominous for European security, too, in terms of geographic proximity and defense.

Prof. Thomas Diez from the University of Tubingen believes securitization has replaced “humanitarianism and a spirit of cooperation,” something that he calls “regressive.” This implies the EU might need to take on a more direct and forceful responsibility in order to prevent the nascent instability and violence at its doorstep and beyond. As of March 2023, the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated that “There needs to be a peaceful settlement in terms of the territorial integrity of Armenia and Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh citizens’ right to self-determination. These principles are equally applicable.”

Thus, even though Karabakh has been emptied of its indigenous Armenian population, Karabakh Armenians continue to be the bearers of the right of self-determination. Hence, at this stage, what matters most is to disentangle the possibility to implement the right from being the bearer of it. To claim that Karabakh Armenians used to have the right to self-determination when they populated Karabakh but do not possess the same right after their forced migration would mean to claim that the loss of Ukrainian territories used to be a matter of Ukraine’s territorial integrity as Ukraine is not territorially integral after the Russian invasion.

Hardly anyone would argue that a territory without a permanent population and institutions of self-government could be a state even though a territory is a must for a fully-fledged country to function properly. In a similar fashion, a separate legal-institutional entity and a social body with no fixed abode do not constitute a state by some definitions but continue to be a bearer of rights. According to the Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions, “state formation is not a once-and-for-all process nor did the state develop in just one place and then spread elsewhere. It has been invented many times, had its ups and downs, and seen recurrent cycles of centralization and decentralization, territorialization and deterritorialization.”

On a geopolitical plane, it is safe to assume by losing Artsakh the Russians lost a strategic foothold in a geopolitically and civilizationally significant region. In this context, as well as considering Armenia’s membership of Russia-led blocs and unions, one might be tempted to argue that the defeat of the Armenians was equally the defeat of Russia. Despite this, after an alliance agreement was signed between Russia and Azerbaijan, media portray a Russia that is closer to the oil-rich autocracy-Azerbaijan-than its traditional ally, Armenia.

In the wider context of security, human rights and international law, however, the West, particularly the EU, will also be adversely affected by the irrevocable losses of the Armenians in the long term. In addition to the fact that a weak and vulnerable Armenia is easy prey for regional powers, the EU will have to save its own face as a reliable alternative to Russia given its inability to prevent or cease the forced exodus of the Armenians of Artsakh. What’s more, political matters are further compounded by an admixture of Armenia’s dependence on Russia, geopolitics and multilateral civilizational ties that are bound to have a long term impact on Armenia’s perception of its self. Hence, a more engaged and vociferous Europe would guarantee Armenia’s “dual alignment,” a concept propounded by Stefan Morar and Magdalena Dembińska.

Nevertheless, short-term calculations seem to dominate the regional political scene against the backdrop of the geopolitical turbulence caused by the on-going conflict in Ukraine. Some officials from the Russian Duma went so far as to approve of the dissolution of the de-facto state from the perspective of putting an end to hostilities, something that masked a Russian failure to admit the tragic consequences of their peace-keepers’ inaction.

To make matters worse, it became obvious that the international law and institutions undergo a major structural shift-resolutions of supranational bodies and courts fall on deaf ears, while human security is increasingly vulnerable and largely unprotected. To be precise, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted Resolution 2508 on June 22, 2023, which explicitly stated that, “since 12 December 2022, the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh, in Azerbaijan, has been denied free and safe access through the Lachin corridor, the only road allowing them to reach Armenia and the rest of the world. This has had serious human rights and humanitarian consequences, notably regarding freedom of movement, non-discrimination, access to healthcare and food, the right to family life and to education.”

The adoption of the resolution preceded a large-scale aggression against Artsakh in September 2023, which was strongly condemned in another resolution of the Council of Europe. Interestingly, in its declaration that condemned the Azerbaijani military operation against the people of Nagorno-Karabakh adopted on October 17, 2023, the Spanish Senate explicitly admitted the death of hundreds of Armenians, a massive exodus of the population (which implies forced displacement) and reminded Azerbaijan of the fact that it is a party to the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, a rstraightforward allusion to the genocidal nature of the aggression. Earlier in the year, on February, 22, the International Court of Justice “ordered Azerbaijan to take all necessary measures to ensure unimpeded movement of persons, vehicles and cargo along the Lachin Corridor in both directions.”

Unfortunately, the power dynamics in the region resulted in a catastrophe that has further exacerbated the situation. As a result of the combination of Russian inaction and Western feeble attempts to discipline Azerbaijan, an energy-rich precious partner of some of Europe, the region was emptied — through horrific crimes — of its indigenous population for the first time in millennia. Furthermore, Many ancient Armenian Christian monuments — a beloved cultural patrimony of native Armenians-are now in danger of destruction or appropriation (the precedent was set back in 2006 in Old Jugha, Nakhijevan).

A look at the past reveals the Armenians have traditionally tried to please both the West and Russia in the hope that the inalienable right to self-determination will eventually triumph. Victorious but equally short-sighted diplomatically, the Armenians could have adopted a much more robust diplomatic stance, perhaps a much less desirable foreign policy option from the perspectives of Moscow and the West but a more surefire way to be understood in major capitals in terms of national interests and aspiration. Why was the legitimacy of the pre-war NKR borders not a subject of negotiations considering the fact that the territories adjacent to Nagorno-Karabakh were not even firmly embedded in Azeri jurisdiction?

To reaffirm his constructive and flexible but staunchly pro-Armenian profile, Armenia’s former president Serzh Sargsyan, who was ousted as a result of the Velvet Revolution of 2018, wrote an article on July, 6, 2021 stating that, “the international community should not recognize the outcome of the Turkish-Azerbaijani aggression but it should make efforts to reach a real, comprehensive and long-lasting resolution.”

In a similar fashion, President of NKR, Samvel Shahramanyan, who had signed the decree of the liquidation of NKR earlier, told journalists and angry protesters later in Yerevan, “the Republic of Artsakh is not liquidated. No document can liquidate what was established by people.” Obviously, Mr. Shahramanyan, too, referred to the right of self-determination and the possibility of legal-institutional existence of the Republic of Artsakh upon its physical disappearance.

This means Samvel Shahramanyan can potentially rescind his own order regarding the liquidation of NKR and be deposed, reelected or otherwise subject to institutional checks on the part of the National Assembly of Artsakh whose members might not be in Nagorno-Karabakh any more but continue to the elected representatives Karabakh Armenians.

For around three decades, at least since the inception of the contemporary stage of the conflict in 1988, the Armenian side believed its claim to national self-determination was well-grounded in the context of international law, hence inviolable. With the benefit of hindsight, it might have been more prudent of the Armenians to take the bull by the horns and condemn Joseph Stalin’s policy towards the political fate of Nagorno-Karabakh. After all, the policy of decolonization spearheaded by the UN in the 20th century had ushered in the series of independences. Why did the arbitrary transfer of Nagorno-Karabakh to the jurisdiction of Soviet Azerbaijan have to be discussed outside the realm of decolonization when it met at least some of the criteria espoused by the UN?

Ironically, the Soviet Constitution stipulated the right of self-determination, too, and while it was obvious such a possibility was more political than legal, it made the Armenians contemplate political realities in the light of legally admissible frameworks shrouded in intangible realism. This policy of pleasing both Russia and the West, disarticulating national interests and a highly amenable foreign policy would mask the deep-running inconsistencies for decades to come. Indeed, Yuri Barseghov, an award-winning Soviet professor of international law and a former member of the United Nations International Law Commission, published a book back in 1990-before the collapse of the USSR, linking self-determination to the ideology of Vladimir Lenin, which had later been turned upside down by the arbitrariness of Joseph Stalin. Thus, at an odd crossroads of history the Helsinki Final Act was, at least with regard to national self-determination, related to Lenin’s ideology or so the Armenians might have thought.

After centuries of statelessness the Armenian diplomacy was in a precarious condition upon independence. It had to grapple with the formidable West and jealous Russia at the same time paving the way for the recognition of its rights. Nevertheless, it seems the Armenian diplomacy miscalculated the possibility of the long-term concentric evaluations of Russia and the West making a strategic blunder: Russia and the West would not always agree and, by extension, would not always perceive Armenia’s duality approvingly. To be specific, Armenians gave up on the idea of the reunification of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast with the homeland. Further, they neither recognized the independence of Nagorno-Karabakh nor brought the issue of the legitimacy of its post-1994 borders to the table of negotiations.

“What is the way forward ?” one might ask. A government in exile? Recognition of NKR in pre-war borders? A new cycle of international mediation aimed at the implementation of self-determination and return of Karabakh Armenians? We are convinced that reversing “de facto, then de jure” will not turn back the time but will celebrate and perpetuate the right of Karabakh Armenians to determine their fate in their homeland. And this comes at a moment in history when the EU needs to prove its status and reach as a great power to be reckoned with.

(Garik Poghosyan is a PhD candidate at the Public Administration Academy of the Republic of Armenia in political science. In 2021 and 2022, he taught political anthropology to master’s students in the same institution. He teaches English at Global Bridge Educational Complex in Yerevan.)