By Benyamin Poghosyan Published in The Armenian Mirror of Spectator

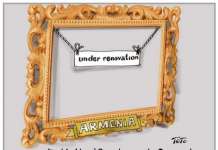

After the military takeover of Nagorno Karabakh by Azerbaijan in September 2023 and the forced displacement of Armenians, there were some hopes in Armenia and abroad that an Armenia – Azerbaijan peace agreement was within reach. These hopes were based on the assumption that Azerbaijan received everything it could dream of just a few years ago.

After September 2023, Azerbaijan controlled the entire Nagorno-Karabakh, with only a handful of Armenians remaining there. The Armenian government accepted that reality with no intention to challenge it, while the international community did nothing tangible to punish Azerbaijan or create conditions to bring Armenians back. President Ilham Aliyev proved to everyone that he was not a “golden boy” who became president just because he was the son of a prominent leader – Heydar Aliyev – and lacked basic governance skills. He succeeded where his father failed, taking control over Nagorno Karabakh and raising Azerbaijani flags in Shushi and Stepanakert.

It seemed that the time had arrived to make peace with Armenia – a peace that would cement Azerbaijani control over Nagorno Karabakh and open the way for Armenia–Turkey normalization. Normalized relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey might allow Armenia to take tangible steps to decrease its dependence on Russia. Economically, Armenia might replace Russian gas with imports from Azerbaijan and divert some of Armenian exports going to Russia to Turkish markets. In the security realm, normalized relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey would probably make the presence of a Russian military base and border troops in Armenia less necessary. Thus, by signing a peace agreement with Armenia, Azerbaijan might pave the way to a more stable region and less Russian presence in the South Caucasus.

The EU and the US may have had these hopes in late September 2023. They looked forward to the triumph of Western facilitation efforts – a signature of the Armenia – Azerbaijan peace agreement and the beginning of the end of the Russian presence in the South Caucasus. Four months have passed, but the peace agreement has not been signed yet, and there are growing doubts that it may be signed soon. The reason is not Armenia’s reluctance or Armenia’s demands to secure the right of returns of Armenians to Nagorno Karabakh, to provide autonomous status to Nagorno Karabakh, or to withdraw Azerbaijani troops from occupied territories of Armenia.

The primary reasons are Azerbaijan’s demands of an extra-territorial corridor via Armenia from Azerbaijan to Nakhijevan, Azerbaijan’s rejection to agree on concrete maps for delimitation and demarcation process, and the Azerbaijani de facto refusal to recognize Armenian territorial integrity within Soviet Armenia administrative borders, despite the fact that Azerbaijan signed numerous statements in Brussels on accepting 1991 Alma-Ata declaration as a base for defining borders.

By putting forward these demands, Azerbaijan effectively killed the possibility of signing a comprehensive agreement. As an alternative, Azerbaijan offers the possibility of signing a “framework agreement,” which will leave open all outstanding issues between Armenia and Azerbaijan while cementing the post-September 2023 status quo. Even if a framework agreement is signed, the region will mostly stay the same. It will not bring lasting stability, keep the door open for military escalation, and not open the way for Armenia – Turkey normalization. Azerbaijani behavior makes it clear that Baku is not interested in having peace in the South Caucasus, even a peace which will be based on the complete victory of Azerbaijan in the Nagorno Karabakh conflict, a so-called “victor’s peace.”

There could be several explanations behind this behavior of Azerbaijan. From a domestic political perspective, President Aliyev may need to continue to have external enemies as a factor to rally the population behind his rule. In this scenario, the concept of “Western Azerbaijan” may replace Nagorno Karabakh, making the return of Azerbaijanis to Western Azerbaijan or actual Azerbaijani control over it a new national dream, similar to the “liberation of Karabakh.”

Another explanation could be Azerbaijan’s desire to continue to weaken Armenia and, as the end goal, to make Armenia a non-viable state by creating a land border between Azerbaijan and Nakhijevan through Armenian territory and closing the Armenian border with Iran. There could be other explanations, too. However, one thing is clear. Nagorno Karabakh was only one piece of the bigger puzzle of Azerbaijan’s and probably Turkey’s strategy towards Armenia. It means that even if Armenia accepts all demands of Azerbaijan, including the establishment of the extra-territorial corridor, “return of enclaves,” deployment of Azerbaijanis into Syunik and other regions of Armenia, and others, Azerbaijan will not sign a deal and will put forward new demands. It will be a never-ending story, weakening Armenia more and more.

Armenia is now in a very challenging situation. After the complete takeover of Nagorno Karabakh by Azerbaijan, the Syunik, and Vayots Dzor regions are sandwiched between Azerbaijan and Nakhijevan, military balance continues to remain in favor of Azerbaijan, Russia – Armenia relations have been at their lowest point since 1991, and the EU and the US have not offered any viable hard security guarantees. This situation requires prudent and calculated actions from Armenia. However, one thing is clear, the continuation of the appeasement policy toward Azerbaijan will not solve Armenia’s problems and will only worsen the situation.