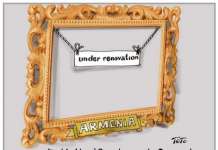

Some mega-millionaire philanthropists fund universities and hospitals, while others opt to fund immunization campaigns. But in Armenia, the super-rich seem to prefer building churches.

So far in 2015, some of the country’s most powerful and wealthy public figures, none of them known for being particularly pious, have provided funds for work on five churches. Tycoon Gagik Tsarukian, founder of one of the country’s largest political parties, Prosperous Armenia, accounts for two of the five houses of worship – in Nubarashen, a district of the capital, Yerevan, and Nor Hachn, a town outside Yerevan. Overall, Tsarukian has been involved in the building or reconstruction of seven churches since 2000, spending estimated tens of millions of dollars.

Elsewhere, millionaire Prime Minister Hovik Abrahamian and his family, which has interests in the country’s food sector, contributed a church to their southwestern seat, Artashat. In June, French-Armenian philanthropist Sarkis Petoian built a church in the eastern lakeside town of Sevan. Meanwhile, Russia-based billionaire and real-estate magnate Samvel Karapetian funded a church in the capital, Yerevan.

In seeking to explain why church construction has become a popular philanthropic activity in Armenia, some observers cite the fact that the Armenian nation in 301 AD became the first to adopt Christianity as their official religion, adding that religion continues to play a central role in Armenian history and cultural identity.

Other factors might also be in play. For example, the church financed by Abrahamian and his family opened in Artashat while Abrahamian’s son, Argam, was running for town mayor. (Armenian law allows charitable donations by public officials.) The junior Abrahamian, a son-in-law of fellow church-builder Tsarukian, won the vote.

Overall, since 1999, roughly 250 churches and monasteries have been built or restored, according to the office of Catholicos Karekin II, the spiritual leader of the Armenian Church.

The benefactors are reluctant to discuss specifics about their donations. “We have never publicized what kind of financial investment has been made in the sphere of church construction because it has been done purely out of devotion, so we were not willing to give it a material value,” said Iveta Tonoian, director of the Gagik Tsarukian Charitable Foundation, the entity that oversees the tycoon’s church-construction projects.

Real-estate mogul Karapetian could not put an exact figure on his investment. “I can’t answer exactly; maybe several million [dollars],” he told journalists at his church’s April groundbreaking ceremony.

Armenia’s tax code allows charities to receive a sales-tax exemption for any purchased supplies, financial transfers or work done for building a new church. Benefactors also do not pay taxes on the purchase of land where the church will be located. Individuals can take an income-tax deduction for charitable donations that do not exceed a quarter of a percent of their total personal income tax.

The Armenian Apostolic Church is responsible for the cost of paying for clergy and maintaining the buildings – expenses that can run into the tens of millions of dollars, former prime minister Hrant Bagratian, who now serves as an opposition MP, said in parliament this May. The church disputes that figure.

The church does not examine the sources of financing for the churches it consecrates, noted religious-rights advocate Stepan Danielian, chairperson of the non-profit Cooperation for Democracy. “This is the kind of field where you can launder money and not be asked a single question,” Danielian posited.

Representatives of the Armenian Apostolic Church insist that no dirty money is involved in church construction. “If the money came from criminal sources, the Church would never accept it, but in these cases [of businessmen-financed churches], who are we to judge?” said Bishop Bagrat Galstanian, director of the Office on Ecclesiastical Liturgical Issues at Etchmiadzin, seat of the Armenian Apostolic Church. “Let’s not forget about the presumption of innocence.”

Construction of the tycoon-funded churches provides work for Armenian quarries, manual laborers, and artists as well as clergy and support staff, Galstanian added.

In a country where the official unemployment rate is 21 percent, the construction of churches has prompted questions about misplaced priorities. In Nor Hachn, site of a Tsarukian-funded church, Marineh Karapetian, whose husband once worked at the town’s shuttered diamond factory, complained that “a plant should have been built, rather than a church.” With a reopened diamond factory, “some 500 people would have jobs,” she added. “Wouldn’t we pray more arduously in that case, and praise Tsarukian with more love and gratitude?”

Galstanian, the church spokesman, maintains that demand for new churches is real. “[I]t does not really matter who has commissioned [a new church],” the bishop stressed, “because it is an eternal value and what matters most is how beneficial the new church can be to people, [and] what service it can provide to society.”