Perseverance and vigilance pay off. Armenians around the world have struggled for a full century to get 30 countries to recognize the Armenian Genocide. And even more importantly, the centennial commemoration in 2015 achieved global resonance with Pope Francis I, who called the event by its true name, and four heads of state arrived in Yerevan to participate in the commemoration at Tsitsernakaberd. And last, but not least, last October, when a historic opportunity arose, both chambers of the legislative branch of the US government passed resolutions recognizing the Armenian Genocide, which had remained elusive in the US.

Perseverance and vigilance pay off. Armenians around the world have struggled for a full century to get 30 countries to recognize the Armenian Genocide. And even more importantly, the centennial commemoration in 2015 achieved global resonance with Pope Francis I, who called the event by its true name, and four heads of state arrived in Yerevan to participate in the commemoration at Tsitsernakaberd. And last, but not least, last October, when a historic opportunity arose, both chambers of the legislative branch of the US government passed resolutions recognizing the Armenian Genocide, which had remained elusive in the US.

International relations are structured in such unexpected ways. Therefore, the name of the game is to keep the forces at the ready and informed, so that when those opportunities come, they don’t bypass us unnoticed and unused.

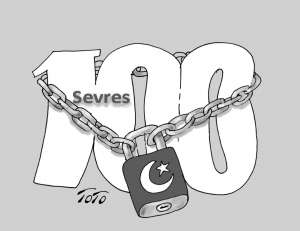

This year presents another historic watershed anniversary to remind the global political community of the injustices committed by replacing the Treaty of Sevres of 1920 with the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923. The specter of the Treaty of Sevres has haunted the leaders of the Republic of Turkey for a full century.

Let’s present some background. In the immediate aftermath of the Armenian Genocide, the Treaty of Sevres came to bring justice to victims and survivors of that genocide within the historic boundaries of Armenia.

US President Woodrow Wilson issued his Fourteen Points to create a new world order based on peace and respect for human rights. The 12th point referred to Armenia in the following context: “The Turkish portion of the Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development.”

President Wilson assigned the King-Crane Commission under Gen. James Hardbody to study the case, to determine the borders and make recommendations.

The commission came up with a conclusion to allocate a territory of 150,000 square kilometers to Armenia (versus the 30,000 square kilometers of current Armenia) to include the provinces of Van, Bitlis, Erzurum and Trabzon, with the latter to serve as Armenia’s outlet to the Black Sea.

These recommendations were incorporated in the documents of the Treaty of Sevres (Articles 88 through 93).

As a side show to the negotiations in Sevres, Armenians were struggling to achieve another national dream by creating a home rule in Cilicia, which was not included in Wilson’s recommendations.

The head of the Armenian National Delegation, Boghos Nubar Pasha, had negotiated with the World War I Allies and contributed to their efforts by recruiting a 5,000-strong corps of Armenian volunteers, in return for a guarantee of home rule in Cilicia.

The representative of the Armenian National Delegation in Cilicia, Mihran Damadian, tried to pre-empt the signing of the Sevres Treaty on August 10, 1920, by declaring independence for Cilicia on August 6, 1920. Unfortunately, that act of defiance was not backed by armed forces, because the French authorities had disarmed Armenian volunteers right after their victory in Arara, Palestine, on September 19, 1918, against the combined Ottoman-German forces. Therefore, it was no problem for the French army to dismiss the cabinet members of the government to be led by Damadian.

This historic event reminds us that any time in the future Treaty of Sevres is discussed, the Cilician claim must remain part and parcel of the negotiations.

Although Turkey had signed the treaty, whose Article 88 stated that “Turkey recognized Armenia as a free and independent government,” soon events took a negative turn.

The Allies had assigned Mustafa Kemal Ataturk to go and disband the defeated Ottoman army. Instead, he used that force to begin his “National Liberation Campaign” to rid Anatolia of its remaining indigenous populations. By that time the Alliance had fallen apart with each nation trying to have its separate deal with the resurgent Milli movement. Particularly damaging was the Kemal-Lenin cooperation, which brought ammunition, supplies and gold from Russia to enable Kemal to expel 150,000 Armenians who had returned to their homes in Cilicia. In September 1922, he literally dumped the Greek-majority population of Smyrna into the sea after burning the city and signed the Treaty of Lausanne which gave legitimacy and sovereignty to the current Republic of Turkey. Thus, the Treaty of Sevres was supplanted by the Treaty of Lausanne, in which Armenia’s name is not even mentioned.

The Treaty of Sevres was meant to partition Turkey and return parts of its confiscated territories to their rightful owners. Until World War II, Turkey felt safe from the danger of partition. At the end of that war, however, some provinces were demanded to be returned to Armenia and Georgia. Soviet leader Josef Stalin was even ready to invade Turkey, but when Winston Churchill dangled the threat of the atomic bomb, Stalin halted his efforts.

The Treaty of Sevres can be resurrected anytime that international relations warrant as its reverberations still echo. For example, today there are calls in the Russian parliament to abrogate the Treaty of Kars of 1921, which had finalized the border between Turkey and the Soviet Union. Since the collapse of the Soviet Empire, Russia does not have a common border with Turkey. By virtue of Armenia’s membership in the Soviet Union, Kars remains in force in determining its border with Turkey. By asking Armenia to sign the Zurich Protocols to reestablish relations between the two countries in 2009, Ankara intended to trap Armenia to reconfirm its adherence to that treaty. (Armenia did not sign them.)

Thus far, Armenia has refused to commit itself, allowing Ankara to try to guess Armenia’s intentions. The reconfirmation of the Kars Treaty will revive the conditions which were forced upon Armenia by the Turks in 1920 by the Treaty of Alexandropol.

Thus far, Turkey has enjoyed the fruits of its membership in NATO. But it seems that Ankara has overplayed its hand through its solo adventures in Iraq and Syria while under the banner of NATO. One sign that Ankara has been wearing out its welcome within NATO was the recent votes by the US Congress.

Before even raising the possibility of revising or reversing the Sevres Treaty, the question is how can Armenians receive restitution or compensation?

Turkey has murdered two-thirds of the Armenian nation and confiscated its historic homeland and today enjoys immunity against any legitimate claims, under the protection of NATO. Some legal scholars cannot find a venue to take on the restitution issue.

Others, life Prof. Alfred de Zayas, former Secretary of United Nations Human Rights Commission, have a more optimistic view by stating: “Because of the continuing character of the crime of genocide in factual and legal terms, the remedy of restitution has not been foreclosed by the passage of time. Thus, the survivors of the Genocide against Armenians, both individually and collectively, have standing to advance a claim for restitution. This has been the case with the Jewish survivors of the Holocaust, who have successfully claimed restitution against many states where their property had been confiscated.”

Time is running out for Armenian interests and Turkey is counting on that factor — oblivion. Plus, many Armenians scattered around the world and with blurred national identities, do not see any practical advantage to their lives by appealing for compensation or even laying territorial claims.

Western Armenians were the victims of Genocide and they don’t have a sovereign state to advance their cause. Only a sovereign state has the legal power to go after restitution. That should be a job for the Republic of Armenia, but that country is looking to improve its diplomatic relations with Turkey without preconditions. They have laid the groundwork for potential rapprochement. Therefore, it is incumbent on the Diasporan Armenians to continue the struggle to keep Armenians alert and aware of their rights and to keep world public opinion informed. Otherwise, historic opportunities may pass us by.

The centennial of the Treaty of Sevres is an opportunity to mobilize forces for the long haul; seminars, lectures, public demonstrations, political actions, news campaigns have to come to commemorate the principles of that treaty and to celebrate their anticipated future success and victory. Edmond Y. Azadian