It is very refreshing to be in Armenia these days, to breathe the fresh air of the spring and feel the happiness and euphoria which are palpable everywhere. There is a carnival atmosphere. Even the cab drivers who serve as volunteer political commentators for their passengers have changed their tune only to praise the brotherly love and mutual respect which are on display.

It is very refreshing to be in Armenia these days, to breathe the fresh air of the spring and feel the happiness and euphoria which are palpable everywhere. There is a carnival atmosphere. Even the cab drivers who serve as volunteer political commentators for their passengers have changed their tune only to praise the brotherly love and mutual respect which are on display.

They swear that people have never celebrated any precedent occasion like this one, neither the declaration of independence nor the liberation of Shushi has been celebrated with this level of jubilation.

People who know Nikol Pashinyan are happy and even those who do not know him, are happier with the turn of events. They have all flooded Yerevan from the villages and provinces with flags, honking their car horns, to contribute to the cacophony which is a pastoral symphony for the general public.

May 8 will remain in Armenian history as the beginning of a new political revolution which began in the streets to gain its legislative validation in the national parliament. The parliamentary session was carried out very smoothly. Some lingering doubts about political maneuvering and machinations in the dark were soon dissipated.

The votes were already counted in the streets during the political bargaining which was taking place out in the open. The head of the Republican faction of the parliament, Vahram Baghdassarian, announced that the party had decided to cast 11 votes for Pashinyan, which brought the figures in parliament for him to 59 votes, with 42 against. The number required for his win was 53.

Ironically, even the 42 negative votes may be taken as a symbol that the takeover of the government was not a total surrender.

It was a textbook case of regime change which can make every citizen of Armenia very proud that political civility is in our culture, especially in view of the recent takeovers of governments in the region in the post-Soviet era. The Maydan Revolution in Ukraine divided the country after President Viktor Yanukovych escaped Kiev in the dark of the night in 2014. The mob invaded his residence to make an ugly show of his golden bathroom in the media.

Georgia experienced two revolutions; during the first one, the republic’s first elected president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia, took temporary refuge in Armenia to save his skin, before seeking a safe haven elsewhere. And later, the Rose Revolution of Mikheil Saakashvili overnight reduced incumbent President Eduard Shevardnadze to a political cadaver.

Of course, the worst scenarios took place Iraq and Libya. In the first case, the loss of a million-plus civilians after regime change must weight on the consciences of former Vice President Dick Cheney and his disciple, President George W. Bush. No one is taking responsibility over the continuing bloodbath in Iraq in the last 15 years.

Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi suffered the torturous fate of Edward II of England (1284-1327), namely a sadistic and protracted public execution, courtesy of Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, National Security Advisor Susan Rice and United Nations Ambassador Samantha Power who forced their “humanitarian” commission of the mission on a reluctant president who wished to avoid a new senseless adventure.

In view of all the above atrocious political acts, Armenia can teach a lesson of political civility to countries suffering from political uncertainty.

Before the votes were counted in the parliament, a few members took the podium. The most important message was given by Vahram Baghdassarian, who was ceding power to Pashinyan on behalf of the Republican Party. His main point was that the current revolution has reduced the values in the society to the narrow choice of black or white, and that a hatred is being generated in the news media and on social platforms.

Pashinyan replied that his goal is to end all hatreds in Armenia and then thanked all the parties who voted for him to become the new prime minister. He was subdued and humbled and did not demonstrate his characteristic exuberance.

Now the political games begin. The constitution allows only 15 days for the new prime minister to form his government and submit it to the president for his approval. If the new cabinet is not approved, there will be a second chance. If again it is not approved, then the parliament must be dissolved.

In his acceptance speech, Pashinyan alluded to holding a snap election after a “reasonable span of time.”

Given Armenia’s current political atmosphere, Pashinyan can win by a landslide. However, time is against him. At this point, Pashinyan’s cabinet will serve as a minority government. The purse strings are still in the hands of the Republican Party which has 55 members in the parliament. Gagik Tsarukyan’s Prosperous Armenia Party, which voted in Pashinyan’s favor, holds sway over 31 candidates. The ARF (Dashnaktsutyun) has seven members. It was part of the coalition government but defected to Pashinyan’s camp when victory seemed imminent for the “Velvet Revolution.” The new prime minister will certainly evaluate the political value of that mid-stream defection.

Elections at this time favor only Pashinyan’s bloc, called Yelk, which has only nine votes in the parliament. The Republican Party will lose miserably after the central election committee is reformed and politicized.

The ARF members in the parliament were a gift courtesy of the Republican Party, which cannot be repeated in fair elections.

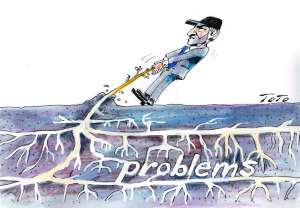

With Pashinyan’s victory, the revolution now begins rather than ends. The challenges lie ahead. The existing problems will not disappear overnight but he has won huge capital in the form of national unity. In those conditions of political adulation, he can pass through any reform.

Among the problems facing the country, the following must be highlighted:

- The national debt ceiling, which stands at $7.5 billion.

- Reform of the economy, which has direct bearing on emigration and the fair distribution of wealth. The latter will lead to bringing into the realm of the law the illegal amassing of wealth, which will impact the oligarch caste. Ironically, some major oligarchs were in Pashinyan’s camp and yet touching their wealth will pose a serious dilemma.

- Dealing with the diaspora. The first question is whether the Ministry of Diaspora will remain. Will all her enthusiasm, former Diaspora Minister Hranush Hakobyan dealt mostly with organized communities in the diaspora, soliciting accolades and dispensing medals. Relations with the diaspora need a more studied approach. A state has to resurrect and reinvigorate its overseas potential. Except for some personal initiatives, nothing was done on a higher level to, for example, awaken dormant Armenians in Turkey. Armenian schools in Javakhk are suffering from a shortage of teachers and textbooks and only lip service has been paid to help them so far.

A major community of 3-4 million remains disorganized in Russia. An extraordinary situation is created in the breakaway region of Abkhazia today an unrecognized republic. In fact, there are more ethnic Armenians in Abkhazia (30 percent) than ethnic Abkhaz people, but the country is ruled by the latter.

Pashinyan’s knowledge of the greater diaspora has proven to be no better. His speeches and connections demonstrate that what he considers to be the diaspora is mostly Glendale, with its large expat population.

Foreign policy is another challenge which needs immediate attention. President Vladimir Putin’s early congratulatory message and Pashinyan’s reassuring statements regarding Armenian-Russian relations are not sufficient and need more concrete actions. Russian news outlets are not comfortable with this takeover and certainly discontent is also simmering on the establishment level domestically.

Now that Pashinyan has successfully crafted the Velvet Revolution, he needs that revolution over his internal life.

In today’s euphoric mood, anything less than a standing ovation for him is considered sacrilege. But, the truth has to be told if the revolution can maintain its arc. Under the slogans of love and respect, there is a rampant hatred towards any detractor. Social media is flooded with observances and below-the belt retorts and innuendoes. If that currant does not stop immediately, it will certainly boomerang and hurt the revolutionaries. The love of this currant was set by Pashinyan himself, who was once Levon Ter-Petrosian’s lieutenant. His performance as the editor of Haykakan Zhamanak was less than stellar. If he does not wish to be on the receiving end of this trend, speedy action is necessary.

Today, Nikol needs to take care of his inner revolution to complete and complement his Velvet Revolution in Armenian society. Edmond Y. Azadian