Ever since gaining its independence, Armenia has been struggling to form a modern democratic society, while trying to improve the economic plight of its citizens. The concentration on domestic issues had left Armenia with a two-dimensional foreign policy, mostly dealing with a hostile neighbor, Azerbaijan.

Ever since gaining its independence, Armenia has been struggling to form a modern democratic society, while trying to improve the economic plight of its citizens. The concentration on domestic issues had left Armenia with a two-dimensional foreign policy, mostly dealing with a hostile neighbor, Azerbaijan.

A major asset of Armenian’s foreign policy was its close relationship with Russia, leading Yerevan to complacency.

This state of affairs turned to be handy for Azerbaijan, which, with its older brother, Turkey, began to isolate Armenia in the region, enlisting in the process the help of Georgia.

Former Georgian leader Mikheil Saakashvili’s administration represented the height of Georgia’s pro-Azeri and pro-Turkey policy. The Turkish-Azeri blockade of Armenia has been exacerbated by Georgia’s collusion to this day.

Armenia only has two narrow borders through which to access the outside world: Georgia and Iran.

Despite friendly rhetoric between Georgia and Armenia, their economic cooperation has failed to reach its full potential.

Turkey and Azerbaijan took full advantage of Armenia’s predicament to tighten the noose of isolation around its neck.

Following the Velvet Revolution, Armenia has exerted determined efforts to emerge from its political isolation. The revolution initially startled Moscow into believing that Yerevan was spinning out of its zone of control, but gradually, a balance has been struck.

Armenia’s democratic reforms have been hailed in European capitals. Armenia has taken advantage of that good will and has been actively cultivating its relations with Europe, with France and Germany being at the forefront, with the Council of Europe in the background.

One sticking point at this time is the new administration’s referendum on an amendment to get rid of the Constitutional Court set up during the previous regime. The referendum is set to take place in April and is expected to win with an overwhelming majority.

However, the Council of Europe’s Venice Commission, the advisory body tasked with tackling constitutional law questions, has expressed its reservations about the drive, believing that Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, after gaining control of the executive and legislative branches of the government, is trying to bring the judiciary under his sway as well.

Beside the above problem, relations with Europe have been developing robustly. To date, Pashinyan has met with Chancellor Angela Merkel of Germany three times. Her visit to Yerevan was very warm and it heated up diplomatic relations. Germany is interested in developing the corridor between the Persian Gulf and the Black Sea, which can bring that region closer to Europe.

During his visit to Germany, Pashinyan met with Secretary General of the Council of Europe (CoE) Marija Pejcinovic Buric, who said to him, “We have already started intensive cooperation between Armenia and the Council of Europe after the visit of the CoE high-level working group last May. I know that you asked the CoE to engage in this process. And the CoE started closely following what is taking place.”

One factor which has contributed to Armenia’s rapprochement with Europe has been the cooling off of relations between Turkey and Europe, and more generally with the entire West.

Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavusoglu, however, announced recently that Turkey will explore new avenues to enhance its chances of joining the European Union.

By the same token, Syria’s standoff with Turkey moved Damascus to recognize the Armenian Genocide. It is worth mentioning that President Bashar al-Assad was one of the few heads of state (alongside President Ahmadinejad of Iran) in the past who avoided visiting the Armenian Genocide Martyr’s Memorial in Armenia for fear of alienating Ankara.

During his recent visit to Germany, Pashinyan announced that he had invited President Hassan Rouhani of Iran to visit Armenia. This seems to be a counterbalance to the recent productive visit of King Abdullah II of Jordan, who is an ally of NATO and the US.

King Abdullah’s visit was significant for renewing old ties with that friendly Arab country that has played a historic role in sheltering Armenians post-Genocide and now seeks a new conduit towards the West.

Armenia has also been credited with enticing Iran to cooperate with the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union.

With these multi-directional relations, Armenia is gradually shedding the label of simply being Russia’s outpost in the region, without alienating Moscow to the point of irritation.

Before moving to another dimension of Armenia’s foreign policy, it is worth mentioning that Armenia’s prime minister met with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev on the sidelines of the Munich World Peace and Security Conference last week.

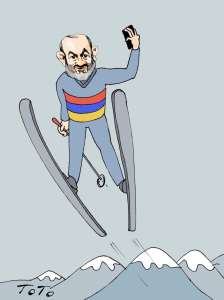

Hopefully, something positive was achieved during their one-on-one meeting. But their public debate was an embarrassment. Pashinyan was ill-prepared and what made matters worse was his use of the English language of which he has poor command. Anyone who tries to convince the prime minister that he had a stellar performance is no friend to him nor Armenia.

The only saving grace was that Aliyev performed no better.

In October, Foreign Minister Zohrab Mnatsakanyan’s interview on the BBC’s “HardTalk” was also heavily criticized.

These two performances pale in comparison to former foreign ministers Vartan Oskanian’s and Eduard Nalbandyan’s public appearances. Their linguistic proficiency matched the excellence of their diplomatic skills. This new administration sorely needs cadres who can represent Armenia in a better light on the world stage.

In line with Armenia’s developing foreign relations is the forthcoming summit with Greece and Cyprus. Again, this is a factor of Turkey’s bullying. The latter occupies a large chunk of Cyprus and has been challenging Greece over the Aegean Sea. But the recent discovery of oil and gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean has galvanized the situation even more. Based on its occupation of Cyprus, Ankara is trying to make good on non-existent mining rights of the so-called Turkish Republic of Cyprus. While initiating its own explorations in the region, Turkey has threatened other parties which have legal rights to the underwater wealth.

Greece and Cyprus have reached out to Israel and Egypt to form consortiums. When Israel’s interests are threatened, the world knows where Washington stands. Despite the US’s implied threats, Turkey is continuing making mischief in the region.

It is a foregone conclusion that those parties facing Turkish bullying need to cooperate with other regional powers. Greece and Cyprus are no match for Turkey. But an international consensus may curb Turkey’s actions. This is how Armenia has been finding its niche in this configuration.

Foreign Minister Mnatsakanyan just met with Cypriot Foreign Minister Nikos Christodoulides. Earlier, he called his Greek counterpart, Nikos Dendias. All these contacts are in preparation for a trilateral summit to be convened this spring in Yerevan. The summit intends to expand the scope of cooperation between these three countries and it will help Armenia to consolidate its firm foothold in the European Union.

Bringing the countries even closer, a contingent of Armenian cadets are already being trained in Greek military schools.

Despite the inexperience of the new revolutionary government, its policy is moving in the right direction, to bring the country out of its political isolation.

It is ironic that Turkey is also contributing to that development, albeit inadvertently.

Edmond Y. Azadian