Armenia’s diplomatic isolation — with its deleterious consequences — has been ascribed to its longtime foreign policy that was solely oriented toward being in line with the Kremlin. Given the political determinants in the Caucasus, Yerevan could not shape and implement a multi-vector policy essential to countries its size.

But the recent tectonic shifts in the Caucasus and Russian periphery have afforded new vistas, along with some risks. With the Russian war launched against Ukraine, Turkey’s influence has grown immensely, while the West has demonstrated renewed interest in the region, mainly to undermine Russia’s influence and eventually cut it off altogether.

Credit was given to President Ronald Reagan and Premier Margaret Thatcher for bringing down the Soviet empire, duping its leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

Today, it is a godsent political opportunity for the West to pursue, and perhaps, achieve another strategic agenda in weakening and dismembering Russia through a war of attrition in Ukraine.

It looks like the days of the Trump era are gone, when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo could cynically satirize Armenia’s woes in the 44-day war launched by Azerbaijan against it and Karabakh, stating, “I hope Armenians can defend themselves.” That page has turned, with President Biden having pledged to return to “perpetual diplomacy instead of perpetual war.”

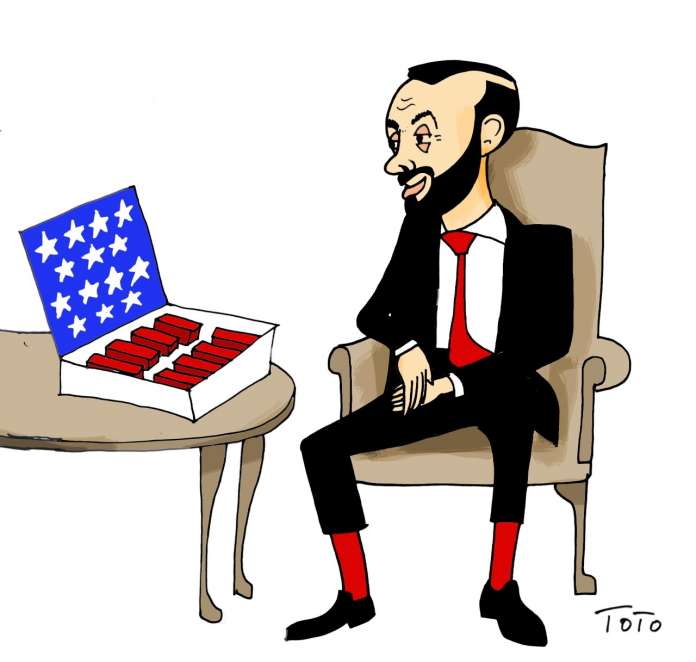

Armenia has become one of the beneficiaries of that policy, with its foreign minister, Ararat Mirzoyan, having been accorded a warm welcome by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, during his four-day working visit to Washington May 2-6.

This initiative comes on the heels of a new diplomatic venture by Armenia. Mirzoyan had just returned from a significant visit to India, exploring economic and defense avenues with that country. In addition to the connection of centuries-old relations between Armenia and India, both countries find themselves in the same situation, targeted by a fanatical Islamic country turned terrorist hub, Pakistan. In the case of Armenia, Pakistan joined forces with Azerbaijan during the 44-day war, while in the case of India, Pakistan plays a role like that of Azerbaijan by seeking a piece of Indian soil, Kashmir. Pakistan is one of the very few countries which still does not recognize Armenia.

While Mirzoyan is visiting the US, the head of Armenia’s Security Council Armen Grigoryan met on May 2 with his Azerbaijani counterpart, Hikmet Hajiyev, to work out the details of setting up delineation and demarcation committees. In his turn, Armenia’s negotiator, Ruben Rubinyan, met with Serdar Kılıç, in Vienna, for a third round of parleys to restore Armenian and Turkish relations.

There was general consensus that those negotiations would not take place without hiccups. Indeed, hurdles are piling up, such as when Ankara pledged to hold negotiations without preconditions and yet relegated its disguised conditions to Baku, which came up with a five-point set of conditions to sign a peace treaty with Armenia.

Right on the eve of the third round of talks between Armenia and Turkey, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavusoglu has come up with the idea that the borders separating the two countries have to be discussed. This is an oblique reference to the Treaty of Kars of 1921, which designated that border, and which Armenia refuses to recognize and ratify.

As Armenia launches its diplomatic offensive to reach out to the West and to India, the window of opportunity is closing on the potential of tapping Middle Eastern countries, as Turkey has already mended its fences with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates and is working actively to achieve the same with Egypt and Israel.

Mirzoyan’s visit to Washington could be considered a breakthrough because it has already achieved its major goals; relaunching strategic dialogue between Armenia and the US and the signing of a memorandum of understanding on the civilian use of nuclear energy, which will diversify resources for Armenia’s energy needs.

Besides all the diplomatic niceties, which looked extremely cordial, Mirzoyan highlighted the most crucial issues by underscoring “the important role the United States play as a co-chair of the OSCE [Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe] Minsk Group, which has a mandate from the international community to facilitate the peaceful resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.”

He also thanked Blinken for the Biden Administration’s recognition of the Armenian Genocide. Exactly one week prior to this visit, Blinken had made the following remarks during a hearing in the Foreign Relations Committee of the US Senate: “I have been very actively and directly engaged with the leadership in both Armenia and Azerbaijan trying to help advance prospects for a long-term political settlement in regard to Nagorno-Karabakh.”

During the same session, he had also blamed Azerbaijan’s unilateral actions which he said “inflame” the situation.

This was a welcome change in the US position, given that past remarks were not targeting the guilty party, letting Azerbaijan off the hook despite its repeated provocations. These remarks are also highly significant in view of the fact that President Ilham Aliyev has been proclaiming that there is no longer a Karabakh conflict, as he has already resolved the issue by force. This will also drop the ball in the West’s court, since Moscow has already been claiming that Karabakh is Azerbaijani territory.

Mr. Mirzoyan also met Samantha Power, director of the US Agency for International Aid (USAID) and as of this writing, he was scheduled to meet Senior Director for Europe at the National Security Council Amanda Slot and other colleagues, to round up the visit delivering a speech at the Atlantic Council and meeting a few key US legislators.

Some people believe this breakthrough was made possible by Ambassador Lilit Makunts, vindicating those who had questioned her diplomatic skills.

Mirzoyan’s visit apparently has created some nervousness in the Kremlin, as Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov has called him to hold a trilateral meeting with Russia and Azerbaijan on May 13, in Kyrgyzstan, on the sidelines of the meeting of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). On the other hand, a pro-Kremlin TV station, Russia 24, has broadcast footage of the demonstrations in Armenia by the opposition, accompanied with clips from the May 1 demonstrations in Paris and Berlin, which have been much more violent than the ones in Armenia.

Incidentally, one would question the timing of the opposition rallies, when Armenia has been negotiating with its enemies and international partners, having existential issues on the agenda.

These demonstrations may become a blessing in disguise if Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan can use them as a bargaining chip with Azerbaijan, indicating that he has a powerful domestic opposition to deal with on the issue of Karabakh, and thus buy time.

When Aliyev has been threatening the very existence of Armenia as a sovereign state, the only option the latter has at its disposal at this time are the tactics to delay signing any peace treaty until its diplomacy bears fruit and it can rebuild its armed forces.

At this time, the OSCE Minsk Group co-chairs are hopelessly divided. But with the renewed interest of the US and France, the issue may enter a competitive phase between Russia and its counterparts. Moscow has made its point on the issue and freezing the Karabakh settlement will ensure its military presence on Azerbaijan’s territory, as long as Moscow’s strategic interest require.

This is a major powerplay in which Armenia has no influence, although its destiny and the future of Karabakh’s people depend on the outcome of this tug-of-war.

The parliamentary opposition has organized rallies with slogans asking Pashinyan to stop delivering Karabakh to Azerbaijan, whereas control of that enclave is not in Pashinyan’s hands but in Russia’s. That is why, perhaps, the opposition rallies promised to culminate on May 1, did not gain momentum, despite the fact that they used a page out of Pashinyan’s own playbook to rouse the masses. The current demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience can hardly match the crowds that Pashinyan was able to galvanize in 2018. By the estimates of the Informed Citizens group, a pro-government party, the crowds did not number more than 12,500, while opposition claims put the number at 40,000 and more. The truth may be somewhere in between.

The opposition leadership seems divided, despite the fact that former Presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serge Sargsyan have joined forces. A charismatic leader has not emerged yet. Their slogans are fuzzy, while Pashinyan, when he was rallying his supporters, created a bread-and-butter issue and slogan. Indeed, alongside the rhyming “Merjir Serjin,” translated into “reject Serge,” Pashinyan claimed that he would expropriate the wealth of the oligarchs repeatedly, to the point that people began to believe that the day after the Velvet Revolution, the privileged oligarch class would be stripped of their wealth, which would be returned to the nation – meaning back in the pockets of ordinary people.

At this time, Pashinyan’s inexperienced team needs internal support to be able to deal with the international challenges it faces and to take advantage of recent developments.

A house divided can only fall. Edmond Y. Azadian