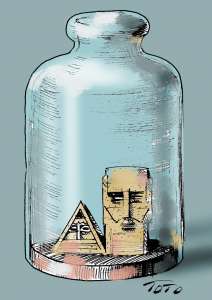

If the pundits thus far have believed that the Karabakh conflict is one of the most intractable problems of our time, now new elements have emerged to render the problem even more convoluted and therefore more dangerous, all under the guise of forthcoming peace initiatives.

If the pundits thus far have believed that the Karabakh conflict is one of the most intractable problems of our time, now new elements have emerged to render the problem even more convoluted and therefore more dangerous, all under the guise of forthcoming peace initiatives.

The first salvo to augment the tensions came from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group co-chairs, the group tasked with bringing the issue to a peaceful conclusion, with a sterner tone than before.

Throughout the negotiations, the co-chairs treated the issues with kid gloves, leaving the initiatives to the parties of the conflict, and agreed to play an advisory role and to consolidate for the international community whatever terms the parties involved found acceptable.

That tone was reversed completely in the statement issued by the co-chairs on March 1. Now an ironclad format is being proposed, and the tone is that of an ultimatum. This transformation seems to be a reflection of the perception of the co-chairs that changes have taken place in the region which are amenable to forcing conditions that thus far have been deemed unacceptable to the parties.

The Azerbaijani government’s positive reaction, contrasting with Armenia’s reservations, if not outright rejection, indicate that the weaker party is Armenia.

We have to be mindful that the co-chairs have been doing their homework all along and are aligning their own self-interests within the framework of the conditions proposed to the parties in the conflict. We should never be so naive as to believe that the co-chairs representing major powers would subordinate their interests to those of the warring parties.

Therefore, Armenia’s standoff with Russia has been factored into the formulation of this new approach. In addition, demotions in Karabakh’s military’s power structure and destabilizing political movements within that republic have been interpreted by the international community to mean that Armenia must be ready to accept terms that thus far it has found inadmissible.

At the height of the recent Russo-Turkish tensions over Syria, there were rumors circulating in Moscow that President Vladimir Putin was contemplating the abrogation of the 1921 Treaty of Kars between Lenin’s Russia and Ataturk’s Turkey which sealed the Armenian-Turkish border. To dispel all those rumors, Putin and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey exchanged some documents, in an atmosphere akin to exchanging love notes. Putin offered a copy of the treaty in exchange for a photograph by Erdogan featuring representatives of the two sides signing the abominable treaty. The exchange took place on March 15, on the anniversary of the treaty. Armenia was not a party to the Moscow signing but was forced to sign it in Kars, in October of the same year.

A seemingly insignificant gesture comes to further elucidate Russia’s uncompromising position towards Armenia; indeed, the abduction by Moscow to Baku of the Talish leader Fahreddin Abuzoda should not be considered a coincidence.

Incidentally Talish and Lezgy minorities are struggling in Azerbaijan to achieve self-determination and their leaders have been languishing in Azeri prisons. Armenians have been rightfully asking Azeri President Ilham Aliyev to set a precedent of allowing the autonomy of those minorities to divulge the nature of the “highest degree of autonomy within Azerbaijan” his government is promising to the people of Nagorno Karabakh.

The OSCE issued the framework of negotiations in preparation for the forthcoming summit between Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and President Aliyev. That alerted the parties to resort to their respective posturing; Azerbaijan unleased its offensive war games (versus defensive) deploying all categories of state-of-the-art military hardware. The Armenian side, on the other hand, decided wisely to put its house in order. The security councils of Armenia and Karabakh held an unprecedented joint meeting, where Pashinyan came out with a powerful statement laying the groundwork of Armenia’s position as well as the conceptual approach to the basic tenets of the negotiations.

The joint meeting was also a powerful statement of unity between Armenia and Karabakh, particularly needed in light of Pashinyan’s insistence on Karabakh’s participation in the negotiations, lest any doubt was left about the unity between the two entities.

Pashinyan’s statement that he was not mandated by the Karabakh people’s vote to negotiate on their behalf should not be construed to mean that there is an erosion in Armenia’s determination to guarantee Karabakh people’s security and self-determination.

Although the Minsk group co-chairs tell the two sides that no new element can be introduced to impede the negotiating process, Russian Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova has stated that Moscow would be willing to entertain Pashinyan’s wish, if both parties agree to it. And this, she has added is the position of all the co-chairs.

All along, the meetings have been characterized as discussions. When the parties engage in negotiations, rather than discussions, recording every element of agreement in the process, Karabakh cannot be left out because its signature will be necessary on the final document.

Currently a very healthy public debate is taking place with the participation of representatives from Pashinyan’s movement and the former regime, incredibly with minimal incrimination against each other.

The press statements of the co-chairs come with a preamble admonishing the parties “to reduce tensions and reduce inflammatory rhetoric.” This refers to Azerbaijan and particularly to Mr. Aliyev. On the other hand, they ask “to refrain from statement and actions suggesting significant changes to the situation on the ground.”

This, in turn, refers to Pashinyan’s insistence on the participation of Karabakh representatives in the negotiations.

Some analysts believe that by the above position, Armenia has been pushing itself into an untenable situation, since Aliyev has refused that proposal out of hand. But Armenia maintains a flexible position by its willingness to engage in negotiations, even without Karabakh’s participation.

Historically, the negotiations have been between three parties: even the cease fire negotiated in Bishkek in 1994 was signed by a Karabakh representative. Armenia has been alone in the negotiations against Azerbaijan since 1997, because Presidents Robert Kocharyan and later Serzh Sargsyan had worn double hats by virtue of their participation in the Karabakh war as leaders.

The trickiest part of the negotiation is contained in the principles laid down in the statement of the co-chairs. Those principles have been discussed time and again in many prior sessions in Madrid, Kazan, Geneva, Key West, and on and on. But today, they have become as crystalized and rigid as final terms for the parties to accept.

The following are those terms:

- The return of the territories surrounding Nagorno Karabakh to Azerbaijan’s control

- An interim status for Nagorno Karabakh providing guarantees for security and self-governance.

- A corridor linking Armenia with Nagorno Karabagh

- Future determination of the final legal statue of Nagorno Karabakh through a legally-binding expression of will.

- International guarantees that would include a peace-keeping operation.

As one may detect easily, these principles mostly favor Azerbaijan. Whatever Azerbaijan could not achieve on the battleground, it is trying to achieve at the negotiation table with the help of the international community. The party which has lost the war is being offered the upper hand.

This reminds one of the aftermath of World War I, when a defeated Turkey was allowed to resurrect itself as one of the most powerful nations in the Middle East, courtesy of the Great Powers.

The above principles come with many loopholes and they need further explanation and exploration. That is why the Armenian side has requested clarification on all the points.

Whatever the Armenian side will lose in the compromise is irreversible. Any territory ceded can only be reconquered through new bloodshed. And vague promises of future autonomy are a non-starter for people who have experienced Baku’s pogroms of 1903 and 1920, as well as in Sumgait and Baku in 1988. A generation which was born and brought up after the Karabakh in an independent, albeit non-recognized republic, will never submit willingly to go back under the Azeri yoke.

Armenians have to be extremely careful in defining the term “self-determination,” in which Mr. Aliyev is offering to the people of Karabakh his utopian vision of the “highest degree of autonomy.” Karabakh is an independent state now and cannot return to the status of an autonomous region under Azeri rule.

There are three fundamental principles and six elements for settlements. The three principles are peaceful methods of negotiations, the principles of territorial integrity and the right to self-determination.

We have issues with the last two principles. The term self-determination is so vague that even Stalin believed that he was granting self-determination to the Karabakh citizens when he defined the Nagorno Karabakh Oblast and handed it as an enclave to Azerbaijan.

On the other hand, the Secretary of the Security Council of Karabakh and the commander of the troops during the war, Vitaly Balassanian, goes as far as to question Azerbaijan’s contention regarding territorial integrity by stating, “Azerbaijan’s territory is very dubious. This country must first prove to the international community what territory it is talking about. This is a very disputable issue and I am convinced that when Artsakh comes forth as a full negotiating side, we will necessarily raise this issue.”

While Armenia is gearing up for the negotiations, calls are getting louder and louder that we have to be ready for war if we wish to achieve peace. Our constant yearning for peace is interpreted on the Turkish side as a weakness. Pashinyan made a very succinct remark that if Armenia is for peace, Azerbaijan’s people also vie for peace. Edmond Y. Azadian