As a new political order shapes up in the Caucasus, Armenia will face new risks and new opportunities. The question is how Yerevan will cope with new realities after suffering the devastating impact of a disastrous war.

Armenia would have been better equipped to deal with such opportunities before the war. Also, there is a serious concern regarding the ability of the current inexperienced leadership to successfully navigate through these turbulent waters and come out a winner.

One of the major developments is Turkey’s apparent change of heart and new desire to make peace with Armenia.

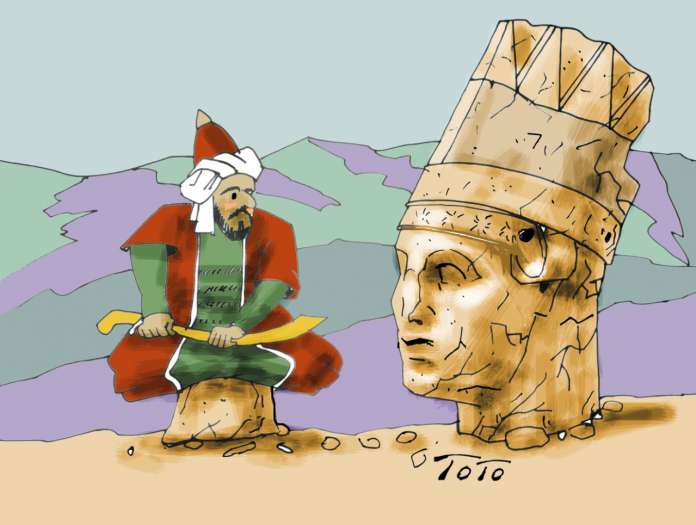

Almost a year ago, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan claimed, during a victory parade in Baku, that he had arrived there to achieve “the goals of his forefathers,” evoking the memory of Enver Pasha, one of the three architects of the Armenian Genocide.

Therefore, a statesman who publicly admits that his political goal is to continue the genocidal intentions of imperial Turkey must have other reasons and motivations to launch a peace initiative with those same people, which cannot be anything but a tactical and temporary retreat from its primary goals. Even if Turkey’s intention is not to commit a new genocide, nor continue the first one, its political ambitions of building a Turanic empire necessitate this detente.

Ruben Safrastyan, a Turkologist at the Armenian Academy of Sciences, states: “Armenia continues to be a wall separating Turkey from ‘Big Turan.’ Turkey signs separate military-technical agreements with all Turkic-speaking states, providing a supply of weapons produced in Turkey to these countries. This is the path, politics, [and] ideology of Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his army, towards the formation of ‘Big Turan,’ which now Turkey quite openly is demonstrating.”

He then goes on to mention that the idea had been earlier promoted by Mustafa Kemal, who had been advocating for Armenia’s destruction by removing “that wall.”

Safrastyan’s cautionary remark jibes perfectly with what the Economist defined as Turkey’s role and goal in the recent war, stating: “Though not mentioned in the trilateral agreement [of November 9, 2020], signed between the two belligerents and Russia, Turkey is a big beneficiary of it. It is to get access to a transport corridor through Armenian territory … linking Turkey to Central Asia and China’s Belt and Road Initiative.”

Thus, when Azerbaijan’s leader Ilham Aliyev insists on the “corridor” through Armenia’s sovereign territory, he is looking to join Baku to Nakhichevan, while Mr. Erdogan’s intentions go far beyond.

These are the parameters within which regional transformations are taking place.

From a position of intransigence, the Turkey-Azerbaijan tandem reverted to a conciliatory mood, purporting to want to make a peace deal with Armenia. One minor factor in this change of heart is that after the war, the Turks can extract maximal concessions from Armenia, but the major component is Turkey’s faltering economy, which helped build up its military might and fueled its imperial ambitions. Writing in the Gatestone Institute publication, Turkish commentator Burak Bekdil states, “Erdogan is heading fast to becoming the victim of his own miscalculations: a dramatically mismanaged economy and geostrategic challenges that went beyond Turkey’s political and military might.”

Indeed, Erdogan’s rule previously brought prosperity to Turkey. In 2002, Turkey’s GDP per capita stood at $3,688 which in 10 years rose to $11,796. Today, it is down to $7,500, reducing 50 percent of the population to below the poverty line.

These dramatic changes have caused domestic political unrest in Turkey and undermined the country’s expansionist ambitions.

Therefore, it was not surprising that Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Çavusoglu announced recently that Turkey and Armenia have decided to begin negotiations to restore peace in the Caucasus. (See related story on Page 1.) However, Armenia is not the only country that is targeted by Ankara’s outreach; that initiative has to be viewed within the context of Turkey’s foreign policy transformation. Turkey may reverse that process any time it recovers from its economic downturn and musters enough resources to return to pursuing Erdogan’s dream.

It turns out that Turkey’s policy change, albeit for tactical reasons, was imposed by the US. Indeed, based on reports from Turkish officials, Bloomberg informs that “Turkey’s surprise overture is in line with President Joe Biden’s request, who allegedly urged Erdogan to open the country’s border with landlocked Armenia during the two leaders’ October meeting in Rome.”

The report also claims that “Erdogan could reap major benefits from any foreign policy move that helps to stabilize the economy as skyrocketing inflation threatens Erdogan’s popularity ahead of the scheduled 2023 elections.”

For all practical purposes, this is virtually an economic rescue plan for Turkey to stop the freefall of the lira and the country’s 43-percent inflation.

Turkey had strained relations with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates when Erdogan anointed himself the sultan of the Sunni world. Those relations were further exacerbated by the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Ankara. These days Foreign Minister Çavusoglu is in the UAE to repair relations. Earlier, a UAE representative had visited Turkey with a $10-billion investment plan and in February President Erdogan is scheduled to visit the Emirates to solicit more help.

Turkey has begun negotiations with another adversary, Egypt, which was alienated because Turkey supported the Muslim Brotherhood, who are considered terrorists in Egypt. Ankara and Cairo almost resorted to an armed conflict in Libya, where both countries maintain interests and back opposite sides. Incidentally, Armenians have benefitted from the standoff between Turkey and Egypt, as the latter opened its archives of the Ottoman atrocities and even the issue of recognizing the Armenian Genocide was presented to the parliament in Egypt.

Turkey is having a tough time mending fences with Israel, although in the past, Turkey was the only Muslim country which had diplomatic relations with Israel, bringing the latter out of regional isolation. But when Erdogan began championing the Palestinian case, highlighted by the Mavi Marmara Incident in 2016, and hosted Hamas leaders from the Gaza Strip, tensions rose and they have yet to recede.

As we can see, Armenia is in good company with all these regional neighbors in conflict with Turkey.

President Aliyev’s conciliatory moves are also a function of Turkey’s political and economic predicament. Just a few months ago, Baku almost went to war with Iran, intoxicated by its victory against Armenia and emboldened by Turkey’s military support, but Erdogan tightened Aliyev’s leash, advising that such support is no longer forthcoming. That is why Aliyev dutifully attended the trilateral meetings in Sochi on November 26 and Brussels in December 14, soft-pedaling the corridor issue at the meeting, however, without any change in his public rhetoric.

Those meetings and negotiations produced an agreement to open a railroad line between Armenia and Azerbaijan, in turn hailed by the US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Spokesperson Maria Zakharova.

Upon returning to Yerevan, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan heralded the cautious beginning of an era of peace in the Caucasus.

Turkey and Armenia have appointed their respective representatives to begin negotiations to unblock all roads and communication lines in the region. Mr. Çavusoglu even has publicly entertained the hope of starting diplomatic relations. To that end, Ankara has appointed diplomat Serdar Kilic as its representative while Armenia came up with its choice in the person of Ruben Rubinyan, an MP from the ruling party Im Kayle (My Step). Turkey’s representative, Kilic, is a seasoned diplomat with four decades of experience under his belt. During his term in Washington as ambassador, he spearheaded genocide denialist campaign in the US legislature.

Armenia’s opposition has been criticizing 31-year-old Rubinyan’s appointment as that of an inexperienced envoy and particularly underlining Pashinyan’s policy of avoiding seasoned diplomats. They blame the administration for appointing one ambassador to the US because she has command of the English language and now this one who is knowledgeable in Turkish, never mind the diplomatic skills necessary for the post.

Armenia is joining the negotiating table in the wrong way by proclaiming that it is willing to negotiate without any preconditions. Instead, it must start negotiations with at least some conditions, although not all may be realistic. One of those conditions must be the recognition of the Genocide. Mr. Erdogan has expressed his condolences on April 24 to the Patriarch of Istanbul during the last couple of years. He can modify his stance by adopting a more acceptable formula.

Armenia must insist on the abrogation of the 1921 Kars Treaty which has set the current borders between the two countries. Armenia must also seek the return, with certain conditions, of confiscated properties from the Istanbul Armenians and also from the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and the Catholicosate of Cilicia in Sis (currently in Antelias). Even if Armenia cannot meet its terms, those demands will become a matter of public record in the world press.

Although Mr. Erdogan has been expressing through veiled remarks that Turkey will come up with conditions, thus far, Mr. Erdogan has been advising Armenia “to behave and learn lessons from the recent war” to meet Turkey’s conditions for negotiations. The Genocide issue should come to the table as well as the Kars Treaty. The constant reference that Ankara will consult Azerbaijan during the negotiations means that Mr. Aliyev will push for the Zangezur Corridor and for a peace treaty with Armenia, forcing the latter to abdicate its claim on Karabakh.

The Armenian side has to keep in mind that Turkey is there with a handicap; it has to deliver if it wants to be in Mr. Biden’s good graces and salvage its economy. Ankara has as much stake in the success or failure of negotiations as Armenia.

Opening the border will help Armenia’s economy but if tariffs and economic restructuring are not in place, Turkish trade may overwhelm Armenia’s economy. There is already an imbalance of trade between the two countries and that may become more alarming.

The Armenian side must sit at the table with the belief that Mr. Erdogan is not doing Armenia a favor by negotiating. It has some self-serving motives above anything else.

The road is replete with minefields and hopefully a durable peace can emerge from the forthcoming negotiations. Edmond Y. Azadian